Understanding the unconscious mind: Freudian & Jungian perspectives explained

The unconscious mind, once the cornerstone of psychoanalysis and early psychotherapy, has seen a decline in popularity with the rise of cognitive approaches like CBT. So, why am I such a big fan? The unconscious is our hidden driver, influencing our thoughts, emotions, and behaviours, often without us realising it. Have you ever thought, “Man, did I really just do that?” Or experienced vivid dreams that left you thinking about it all day?

Let’s explore the basics of the unconscious mind from Freudian to Jungian perspectives. And while they weren’t the original thinkers to conceptualise it, they certainly put it on the map!

The Freudian Perspective on the Unconscious

Whatever way you feel about Sigmund Freud, that man was the OG of the unconscious and for that, I adore him. While it was introduced in psychology by thinkers such as William James and Wilhelm Wundt, Freud popularised it and make it the core part of his psychoanalysis during the turn of the 20th Century. His groundbreaking work on the function of repression in the human psyche revolutionised our understanding of the unconscious. Freud found that the unconscious uses defence mechanisms like repression to protect the individual from psychological distress by keeping troubling thoughts buried, yet these hidden elements then manifest in dreams, slips of the tongue, and neurotic symptoms (Freud, 1900). He believed that the unconscious housed our primal drives, particularly those related to sexuality and aggression, and whatever the conscious mind deemed unacceptable (Freud, 1900). Freud's goal was to bring unconscious material into conscious awareness, enabling individuals to confront and resolve their inner conflicts. This emphasis on the unconscious mind provided a new lens through which to understand psychological distress and paved the way for more dynamic therapeutic techniques.

The Freudian Psyche

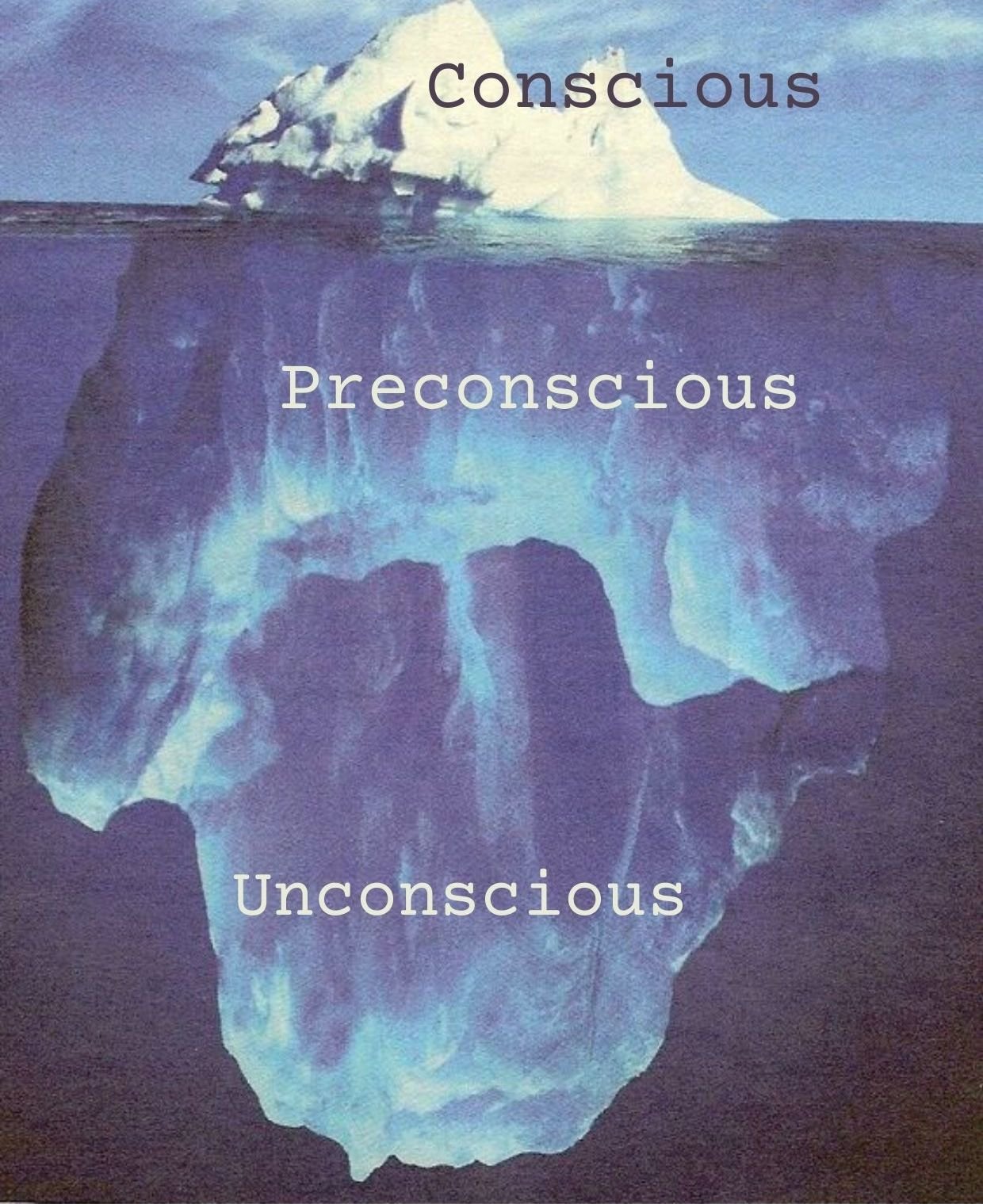

Freud firstly categorised the mind into 3 layers of consciousness (Freud, 1915)

The Conscious mind: This is the part of the mind that holds what we are currently aware of. It includes our thoughts, perceptions, and feelings that we are actively thinking about and experiencing in the present moment.

The Preconscious mind: This layer contains memories and thoughts that are not currently in conscious awareness but can be easily brought to the surface. It acts as a bridge between the conscious and unconscious mind, holding information that we can access if needed.

The Unconscious mind: This is the deepest layer and holds thoughts, memories, desires, and feelings that are not accessible to conscious awareness. According to Freud, the unconscious mind influences our behaviour and experiences, even though we are unaware of its contents.

Freuds discovery of the unconscious mind lead him to develop his structure of the human psyche which comprised of conscious and unconscious parts that communicated with each other, the Id, Ego and Superego (Freud, 1941).

The Id, Ego and Superego explained

Id: This is the most primitive part of the psyche, operating entirely in the unconscious. It contains our basic instincts and drives, such as sexual and aggressive impulses, and operates on the pleasure principle, seeking immediate gratification (The part of you part that says “I kinda wanna get fucked up tonight”).

Ego: The ego operates at both conscious and unconscious levels. It mediates between the demands of the id, the constraints of reality, and the moral standards of the superego. It operates on the reality principle, aiming to satisfy the id's desires in realistic and socially acceptable ways (The part of you that says, “okay but just 2 drinks!”)

Superego: The superego also spans both conscious and unconscious realms. It represents internalised societal and parental standards of right and wrong. It strives for perfection and judges the actions and intentions of the ego, often inducing feelings of guilt or pride (The part of you that says “You absolute bellend, we are never drinking again!!”)

Freudian Slips

And we’ve all heard of ‘Freudian slips’, or parapraxes as Freud named them. These slips of the tongue (or pen, or typed) offer a window into our unconscious thoughts and feelings as they inadvertently slip out, often to humorous effect. These slips occur when conscious intentions are overridden by unconscious impulses or associations (Freud, 1901). For instance, a conversation about the next US president and someone says "erection" instead of "election" could suggest the speaker's unconscious preoccupation with sexual matters influencing their perception of the political process. Freud believed such slips provide a window into the unconscious, where repressed thoughts, wishes, and conflicts reside (Freud, 1901).

(Freud in a slip dress, get it, wahey)

The Jungian Perspective of the Unconscious

Carl Jung, a once student of Freud, agreed with Freuds concept of the unconscious but tweaked and greatly expanded it. He conceptualised the unconscious as a rich source of juicy wisdom and creativity, containing not only personal material but also collective and archetypal material.

Jung’s categorisation of the unconscious is comprised of two main layers:

The personal unconscious: Similar to Freud’s unconscious, Jung’s contains memories and experiences that were once conscious but have been forgotten or repressed. And it notably includes ‘complexes’, which are clusters of emotionally charged thoughts. For instance, a father complex might influence an individual’s relationships and behaviours, stemming from unresolved issues related to their own father.

The collective unconscious: A deeper layer shared by all humans, containing universal memories, symbols, knowledge, and archetypes that are inherent and not derived from personal experience. Archetypes are fundamental, universal symbols and themes that recur across different cultures and epochs. For example, the archetype of the Mother represents nurturing and care, while the Hero represents the journey and struggle toward individuation and self-realisation.

(Photo of Carl Jung at his desk looking like he knows too much)

The Collective Unconscious

Jung's idea of the Collective Unconscious is mind-blowingly brilliant, and modern science is finally catching up to explaining it.

(In-depth blog on the collective unconscious coming soon!)

Jung’s theory posits that the collective unconscious is a reservoir of the experiences of our species, containing elements common and ever present to all humanity (Jung, 1969). It's like an invisible web that has connected us all since the dawn of time. Jung suggests that within every individual lies a shared, universal layer of the unconscious mind, filled with archetypal patterns, myths, and symbols (Jung, 1969). These archetypes aren't formed by personal experience but are pre-existing structures that shape human experience and culture (Jung, 1969). Archetypes, such as the Mother, the Hero, the Shadow, and the Self, are instinctual images and patterns of thought and behavior that recur across different cultures and epochs (Jung, 1969). Jung's extensive study on dreams, both his own and his patients', revealed a collection of reucurring symbols and archetypes with shared meanings.

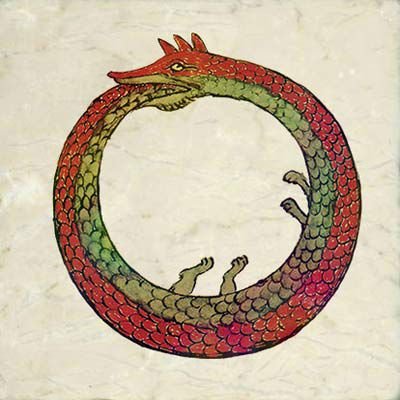

Jung's theory of the collective unconscious was reinforced by his discovery of striking parallels between Chinese and Western alchemical symbols (Wilhelm & Baynes, 2014). Key symbols such as the Ouroboros, the Philosopher's Stone, the Mandala, and the Dragon appear in both traditions, each one representing different concepts of shared meaning in both ancient cultures. For instance, the Ouroboros, a serpent eating its own tail, symbolises the cyclical nature of life and rebirth in both cultures. Similarly, the Philosopher's Stone and the Eastern elixir of immortality both signify the pursuit of eternal life and spiritual enlightenment.

An Ouroboros in a 1478 drawing in an alchemical tract

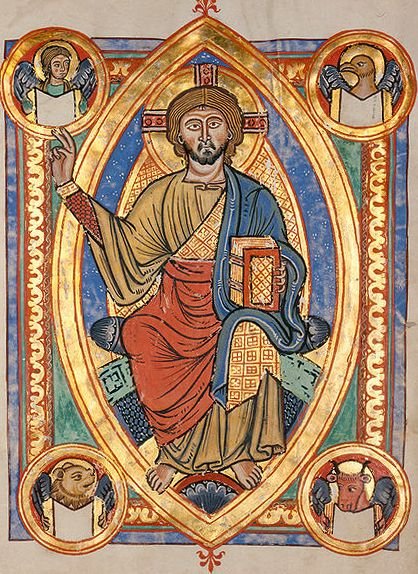

The effects of the collective unconscious can also be seen throughout the astrological aions, as each zodiac symbolises different qualities that influence the culture of that time (Jung, 1968). For example, the archetype of the Self (the totality of a person's integrated psyche) is often depicted in the West as Jesus Christ. The powerful symbol of Christ has influenced the human psyche for the last 2,000 years, as Christ's symbolic wholeness resonates with our unconscious longing to become a unified Self (Jung, 1968). During the prominent time of Christ, the Aion (each Aion lasts around 2,1500 years and begins at the earths procession of the spring equinox) of Pisces was present and had begun during the birth of Christ (Jung, 1968). Pisces, represented by two fish swimming in opposite directions, symbolises duality and the integration of opposites. Jung argued that this astrological age reflects the spiritual and psychological themes associated with the figure of Christ. The Age of Pisces coincides with the rise of Christianity and its themes of sacrifice, redemption, and spiritual transformation. Christ, as a symbol of unity and integration of opposites, reflects the archetypal themes of Pisces, such as merging of the divine and the human, and the spiritual quest for wholeness (Jung, 1951).(Much more on this in future blogs)

Other archetypes can be seen throughout time like the archetype of the Hero can be seen in stories ranging from ancient Greek mythology’s Hercules to modern-day superheroes. The archetype of the Mother is evident in the reverence for goddesses like Demeter in Greek mythology and the Virgin Mary in Christianity (Jung, 1969).

Despite vast cultural differences, the collective unconscious reveals itself through these similar myths, symbols, and narratives. This universality underscores Jung’s idea that these archetypes are not learned but inherent. Cultures across the world have independently discovered and expressed these archetypes, suggesting a shared psychic foundation.

But what about science!?

While direct empirical evidence for Jung’s collective unconscious is hard to pin down, contemporary scientific research offers intriguing parallels. Some studies in the field of neuroscience have revealed consistent brain patterns and responses across different individuals and cultures, indicating a shared neural architecture (Buckner et al., 2008). These findings support the notion of universal mental structures that align with Jung’s archetypal theory.

The field of quantum physics, while not providing direct proof of the collective unconscious, offers compelling metaphors and potential frameworks for understanding interconnectedness. Quantum entanglement, where particles remain connected over vast distances, mirrors the idea of a deeper, non-local connection between all minds (Radin, 2006). This non-locality resonates with Jung’s concept of a shared unconscious.

The Penrose-Hameroff theory of “Orchestrated Objective Reduction” (Orch-OR) suggests that consciousness may arise from quantum processes within the brain (Hameroff & Penrose, 2013). While this is still speculative and not widely accepted, this theory highlights the ongoing scientific quest to understand consciousness, hinting at a potential bridge between quantum mechanics and Jungian psychology.

The golden flower

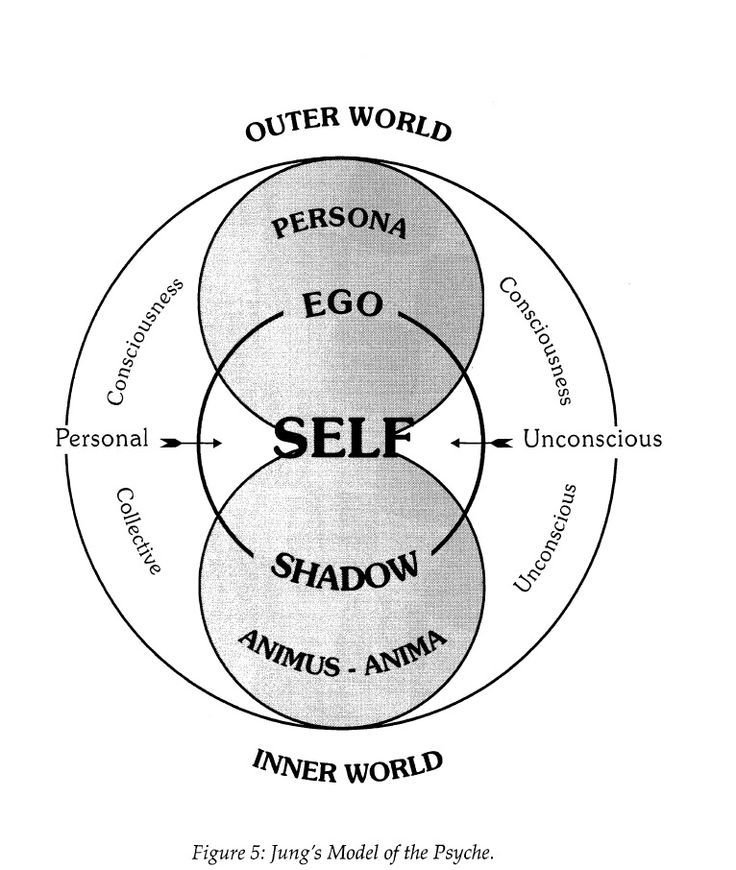

Jung's model of the psyche:

Jung emphasised the importance of the process of individuation, which is the journey toward integrating these unconscious parts into the conscious mind. This process involves recognising and integrating various aspects of the psyche, including the Shadow, Anima/Animus, and the Self (Jung, 1968):

The Ego: The centre of our conscious mind. It is responsible for our sense of identity and continuity, the part that says “I am __”. The ego organises our thoughts, perceptions, and memories and plays a crucial role in how we perceive and interact with the world.

The Persona: The forefront of our conscious mind. The social mask or role that an individual presents to the outside world. The persona helps us navigate social interactions and fulfill societal expectations. However, over-identification with the persona can lead to a disconnection from our true self.

The Shadow: The first layer of the unconscious mind. It represents the parts of ourselves that we reject or deny, often embodying repressed desires and emotions.

(A detailed blog series is coming soon on the shadow and how to integrate it aka shadow work)Anima/Animus: The Anima (in men) and the Animus (in women) serve as bridges to the unconscious because they represent qualities and aspects of the opposite gender that are underdeveloped or less integrated into the individual's conscious personality. These aspects aren't necessarily repressed by the ego but have not been as prominently developed or acknowledged. They complement the dominant personality traits and often carry the potential for emotional depth, creativity, and other qualities that enhance psychological wholeness. They are shaped by masculine and feminine archetypes in the collective unconscious as well as by the individuals caregivers in childhood (usually parents of opposite sex to the individual).

The Self: Represents the unified whole of an individual, encompassing both conscious and unconscious elements. The Self is the goal of individuation, where one achieves a harmonious integration of all parts of the psyche.

Jung’s model of the psyche.

The Shadow

The shadow has become an incredibly hot topic in the fields of psychology, personal development and spirituality in recent years. Which is why i’m doing an entire in depth blog series soon. The shadow is a part of the unconscious that contains repressed aspects of the personality. This includes any qualities, emotions, desires, and traits that were once perceived as non-desirable or unsafe to the conscious ego of the person at that time (Jung, 1968). These can be positive or negative traits, depending on the perspective of the individual at the time of repression. For example, as a child, you may have suppressed your desire to be a dancer because your classmates saw it as uncool, and so your need for belonging caused you to bury your desire for dancing into your shadow.

When working with the unconscious, examining the shadow is often advised as a starting point since it is the closest layer to the conscious mind. However, it is important to approach this work only after developing a strong ego. By a 'strong ego,' I mean having a grounded sense of self and the ability to manage your emotions effectively, so you can handle what emerges from the shadow without becoming too overwhelmed. For instance, a traumatic experience that hasn't been processed might be stored in your shadow and remain there until the ego is sufficiently prepared to address it. Therefore, directly probing the shadow is not recommended. Instead, it is advisable to become aware of how the shadow might be communicating with you, such as through its symbolism in dreams or through strong reactions and projections in relationships. (View next blog on “how the unconscious communicates”)

“The psychological rule says that when an inner situation is not made conscious, it happens outside, as fate. That is to say, when the individual remains undivided and does not become conscious of his inner contradictions, the world must perforce act out the conflict and be torn into opposite halves.”

Poster by unknown artist

Jung’s Psychological Types

Another part of our psyche that may be unconscious and could benefit from integration is the opposite of our personality type. Most people have heard of personality types like those in the Myers-Briggs test (INFP, etc.), which developed from Jung’s theory of psychological types. He proposed that individuals have different dominant and inferior cognitive functions, which influence their personality and behaviour (Jung, 1971).

The four primary functions are:

Thinking: Logically and rationally analysing situations etc.

Feeling: Evaluating situations based on your values and emotional responses.

Sensing: Perceiving situations through your five senses and having killer attention to detail.

Intuiting: Perceiving events through patterns, possibilities, and abstract thinking.

Each person typically has a dominant function in either Thinking or Feeling, and Sensing or Intuiting, along with two inferior functions that reside in the unconscious. For example, if someone had a dominant Thinking function, they would excel at analysing data and making decisions based on logic and objective facts. If their other dominant function was Sensing, they would love attention to detail and be meticulous in executing construction plans, materials, and deadlines.

However, if their inferior functions aren't well integrated, they may lack in Feeling and Intuiting. Integrating their Feeling function could involve becoming more empathetic, acknowledging the emotions of others and themselves, and actively listening to others. Integrating their Intuitive function might involve coming up with new creative solutions rather than sticking to traditional methods, engaging in abstract thinking, exploring the ‘what ifs,’ and looking at the big picture or future possibilities.

Integrating your inferior functions can help you become a more well-rounded individual, preventing those neglected qualities from lurking in your unconscious and say unexpectedly surfacing in your romantic relationships as a desperate attempt to be acknowledged. (The nerd in I.T who obsesses over the quirky spiritual girl..)

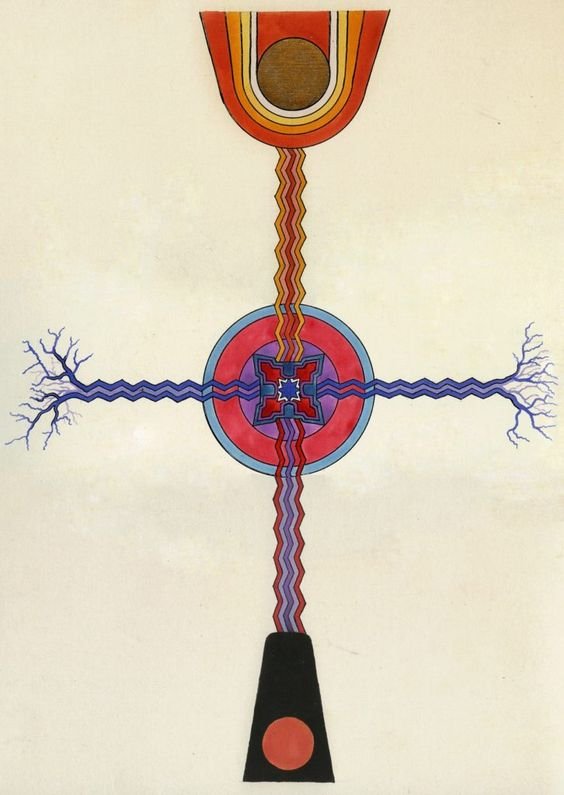

A piece of artwork from Jung’s Red Book that reminds me of the cognitive functions

So maybe now you get a clearer idea of why I value the unconscious so much, understanding your unconscious mind is pivotal for personal growth and understanding yourself. By trying to understand your unconscious you can gain valuable insights into how your hidden mind shapes your thoughts, emotions, and behaviours!

Stay tuned for future blogs on how the unconscious communicates, shadow work, and more!

Thanks for reading :)

And If you’d like to work with me please shoot me a message by clicking here

Sarah Jane Cleary is a psychodynamic psychotherapist located in 24 Patrick Street, Kilkenny, Ireland and online. She is passionate about the power of the unconscious and working with clients to help integrate it, in hopes that they can then lead a more fulfilling and authentic life.

References:

Buckner, R. L., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., & Schacter, D. L. (2008). The brain's default network: Anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124, 1-38. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1440.011

Radin, D. Entangled Minds: Extrasensory Experiences in a Quantum Reality. (2006). Pocket Books.

Freud, S. (1900). The interpretation of dreams (J. Strachey, Trans.). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1900)

Freud, S. (1901). Psychopathology of everyday life (A. A. Brill, Trans.). Penguin Books Ltd. (Original work published 1901)

Freud, S. (1915). The unconscious (J. Strachey, Trans.). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1915)

Freud, S. (1920). Beyond the pleasure principle (J. Strachey, Trans.). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1920)

Freud, S. (1949). The ego and the id (J. Riviere, Trans.). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1923)

Hameroff, S., & Penrose, R. (2014). Consciousness in the universe: A review of the 'Orch OR' theory. Physics of Life Reviews, 11(1), 39-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plrev.2013.08.002

Jung, C. G. (1968). Aion: Researches into the phenomenology of the self (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1951)

Jung, C. G. (1969). The concept of the collective unconscious. In H. Read, M. Fordham, G. Adler, & W. McGuire (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 9, Pt. 1, 2nd ed., pp. 42-53). Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400850969.42 (Original work published 1936/37)

Jung, C. G. (1969). Psychological aspects of the mother archetype. In H. Read, M. Fordham, G. Adler, & W. McGuire (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 9, Pt. 1, 2nd ed., pp. 75-110). Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400850969.75 (Original work published 1954)

Jung, C. G. (1971). Psychological types (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). In H. Read, M. Fordham, G. Adler, & W. McGuire (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 6). Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400850860 (Original work published 1921)

Wilhelm, R., & Baynes, C. F. (Trans.). (2014). The secret of the golden flower: A Chinese book of life (C. G. Jung, Commentary). Inner Traditions.